The Rise & Fall of a Windows Phone Marketplace Scammer

All the latest news, reviews, and guides for Windows and Xbox diehards.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The name Jesse Dudley should be no stranger to the Windows Phone community by now. I mean, WPCentral has been writing about this Marketplace scammer since September. But rest assured you won’t be seeing another post on this subject; I’ve pulled all of his illegal NES games off the Marketplace. Game over, Dudley.

Read what went down, after the break.

Thou Shalt Not Steal

Back when you were a little kid, you may remember Mom or Dad teaching you not to take things that don’t belong to you. (This teaching was oft reinforced via The Belt.) Copyright law at its core is exactly that. Jesse Dudley missed this teaching though and decided it was okay to steal a bunch of NES games, emulator code, and turn it on the Marketplace for a profit.

Dudley’s NES games on the Marketplace comprised of the following stolen and therefore copyright infringing components:

- Logo

- NES Emulator (failed SharpNES attribution)

- Digital copy of retail NES game (ROM).

One widely held myth is that video game ROMs are legal to make and/or use if you own the original cartridge. In the United States, this is completely untrue and has been since 1983, as established in the case of Atari v. JS&A in 1983.

My initial attempts to get these games off the Marketplace, through Nintendo and Microsoft, failed. And without owning any of the stolen content, my hands were legally tied. I nearly gave up.

Can I Has Copyright?

Having struck out with both Nintendo and Microsoft, I decided to focus on the emulator itself. Further research revealed Dudley didn’t just fail to attribute SharpNES developers per the BSD license – he lifted a modified copy of SharpNES code from XDA Developers member Steven Hartgers (fiinix)!

All the latest news, reviews, and guides for Windows and Xbox diehards.

Knowing Hartgers was active on XDA Developer, I knew getting a hold of him would be easy. But a few emails in, I discovered he was in another country. And I knew availing U.S. Copyrights across country borders would introduce a bunch of legal complexities. But after more research, I confirmed copyrights – like any property – can be transferred in part and/or in whole. Hartgers trusted I wouldn’t take his work and build a Fortune 500 company from his assets, so he signed the transfer paperwork and boom – I was the legal copyright holder for all of Hartger’s SharpNES code changes.

Here Comes The Pain Train, Choo Choooo!

Now with the power of the derivative SharpNES code copyright in hand, I felt like a kid with a new set of cardboard boxes. I now possessed the power to avail myself of my newly acquired rights under specific U.S. Copyright law. Yep, I’m talking about that infamously bad-ass Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

The DMCA is a copyright law that includes many provisions, such as those that make it illegal to circumvent copyrighted work protections (e.g. DRM). But it also has safeguards in place to protect websites and service providers from copyright infringing lawsuits based on user submitted content.

For example, Twitter solicits millions if not billions of tweets from users around the world. It’s inevitable that its users illegally tweet copyrighted content. To avoid the onslaught of folks looking to sue the pants off of Twitter for housing that material, Twitter implemented the requirements listed in the DMCA to qualify for protection. One of these requirements is to expeditiously respond to copyright owner requests to take down infringing content. These requests are often referred to as “take down notices”.

Per the Windows Phone Marketplace FAQ, I had to draft a takedown notice and fire it off to Microsoft’s designed DMCA agent. I did just that.

Having sent notices before, I kept my eye glued on the Marketplace, waiting for the applications to go poof. Instead, I received an email from Microsoft 9 hours later, asking me to fill out some cockamamie Microsoft Word form...

The Slow Moving Microsoft Machine

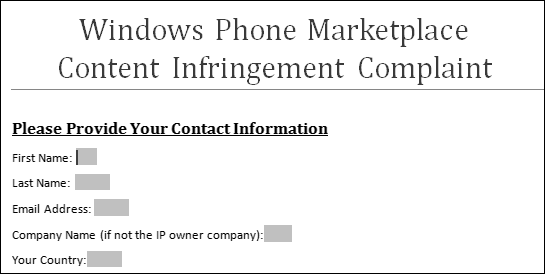

Figure: A snippet of the four page Content Infringement Complaint form I had to complete.

Instead of acting immediately on my DMCA take down notice, Microsoft sidelined me to fill out paperwork to reformat my official request. The four page form used those pesky data fields and was designed to report one application at a time. With 14 applications to report, I refused to fill out the form 14 times. So after a back and forth exchange with Microsoft, they agreed that I could squeeze all 14 applications onto one form. Reluctantly, I filled out the paperwork and sent it in.

I waited impatiently. Days and days had gone by. Nothing seemed to be happening. But finally, a week later, Microsoft pulled Dudley’s applications from the Marketplace. I jumped up from my chair and yelled at my monitor in a Rainn Wilson-like voice: “Shut up, crime!”

(The team actually screwed up and missed one of the applications in my paperwork. And they let enough time elapse allowing Dudley to wiggle another infringing game onto the Marketplace. A quick follow up with more paperwork, however, fixed that problem.)

Aftermath

Having successfully stopped the illegal sale and distribution of Hartger’s and Nintendo’s hard work, I feel pretty good about myself right now. But the process was Ikaruga-hard and I’m still concerned that Jesse Dudley kept the money he stole from others. I’ll continue working with Microsoft on improving this process, but do know it does work – if you’re persistent enough.

Rafael is a Former Contributor for Windows Central.