Windows 10 is 10 years old today — let's look back at 10 controversial and defining moments in its history

From modern app platforms to forced feature upgrades and telemetry concerns, we take a look at 10 of Windows 10's most controversial and defining moments on its 10th anniversary.

All the latest news, reviews, and guides for Windows and Xbox diehards.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

On July 29, 2015, Microsoft launched Windows 10 to the world. It was a step in the right direction after the disaster that was Windows 8, merging the new live tile interface with the familiar Start menu design, and refocusing attention on the desktop experience for keyboard and mouse users.

Windows 10 was the OS of many firsts. It was the first to be built in the open alongside the public, with frequent technical and consumer preview builds on an almost weekly cadence, via a new program called the Windows Insider Program. Users could test and influence development as it was happening, which shaped Windows 10 in a way no previous version of Windows had been.

It would also be the first version of Windows to be updated twice a year with new features and platform changes, be free for existing users coming from older versions of Windows, and transcend the desktop with a new core designed to run on everything from phones to XR devices.

Windows 10 entered full-time development in 2014 under the codename Threshold, a reference to a planet in the video game Halo. It would go on to receive 14 major updates in its lifecycle, with the last major OS release landing in 2022. It was also supposed to be the last version of Windows, but that ended up not being entirely true.

So, to celebrate 10 years, let's look back at Windows 10's most defining and controversial moments that have led us to where we are today.

Windows 10 was free, but only for one (or seven) years

When Windows 10 was first announced, Microsoft revealed that for the first time ever, a new mainline Windows version would be free to upgrade to for existing Windows users.

All Windows 7 and Windows 8 users would be given 1 year to take advantage of this offer. Failure to upgrade to Windows 10 within the first year would mean you would have to pay to upgrade to Windows 10 afterwards. At least, that's what Microsoft wanted you to think.

All the latest news, reviews, and guides for Windows and Xbox diehards.

This time pressure meant that Windows 10 enjoyed an incredible adoption rate in its first year. It achieved 100 million devices in just two months, and that number only increased throughout the first year on the market. This was partly aided by the GWX app, which we'll discuss below.

However, it turned out that the free upgrade period wasn't actually just a year. In fact, the free upgrade was available to all Windows 7 and Windows 8 users until 2023, that's 7 whole years after the free upgrade period was supposed to end!

Even though it was totally possible to activate a Windows 10 PC with a Windows 7 or Windows 8 key in 2023, Microsoft's official stance was that the free upgrade window closed back in July 2016.

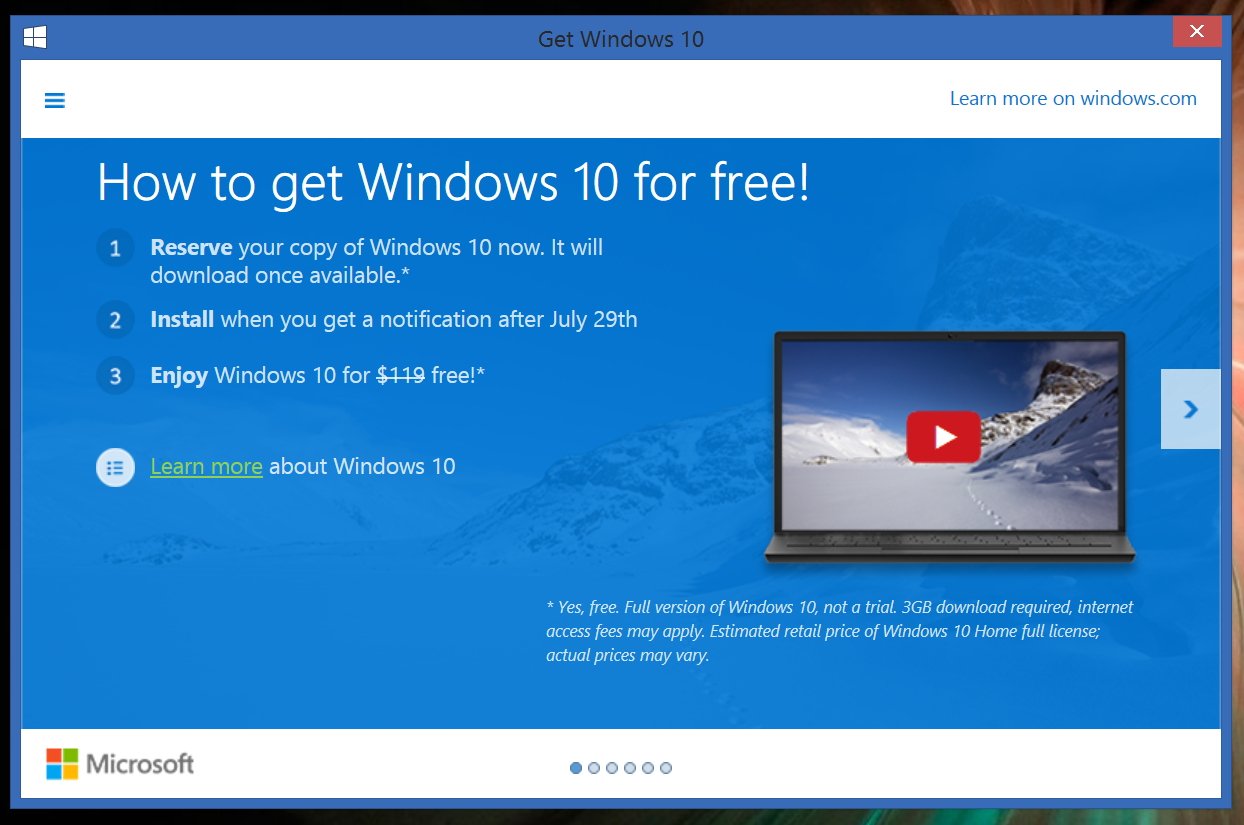

The 'Get Windows 10' (GWX) fiasco

One very controversial move in the early days of Windows 10 was Microsoft's heavy-handedness when it came to upgrading users from Windows 7 to Windows 10. In 2015, Microsoft released an app via Windows Update to Windows 7 and Windows 8 users called "Get Windows 10," internally dubbed GWX.

This app would sit in your system tray and basically harass you into accepting the Windows 10 upgrade. Some reports even claimed that the Get Windows 10 app was forcing upgrades without consent, with several people claiming their PCs had been upgraded overnight while they were asleep.

This app caused a big uproar amongst Windows users who were not interested in moving away from Windows 7 at the time. Microsoft would later admit they were being too aggressive with the Windows 10 upgrade prompts, and later removed the Get Windows 10 app from all Windows 7 PCs.

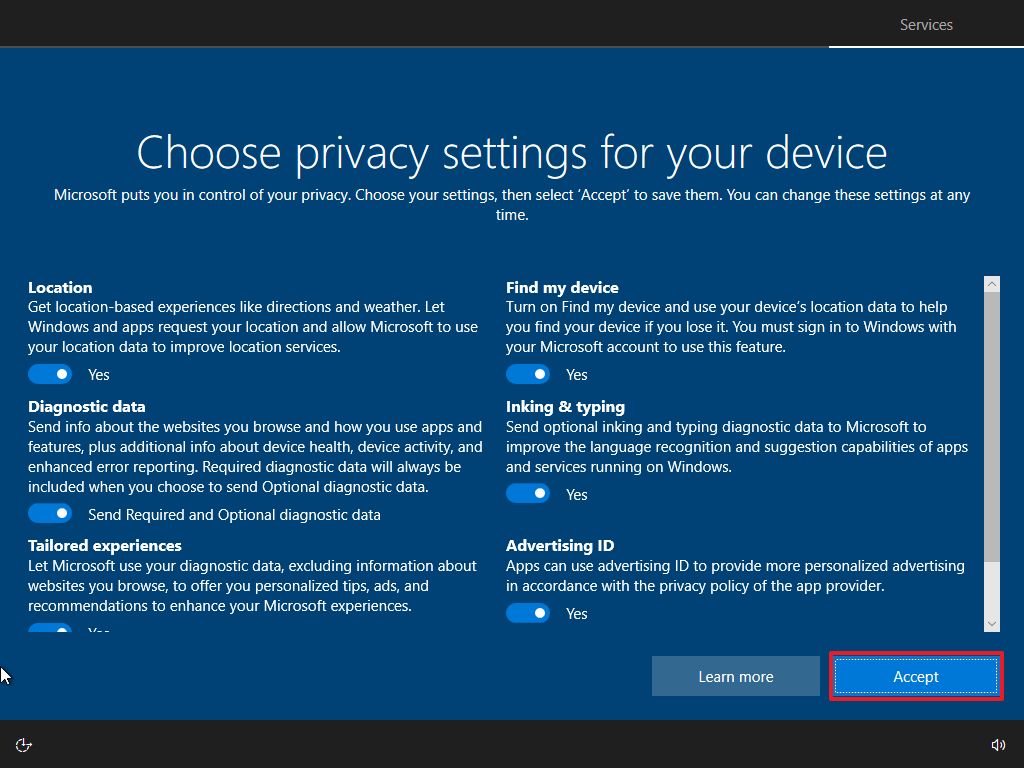

A modern telemetry nightmare

Windows 10 was the first version of Windows to really up the stakes when it comes to privacy and security concerns around always-connected platforms. When the OS first launched, it was criticised heavily for its increased telemetry data collection services, most of which could not be turned off.

That remains true to this day, too. The amount of data Windows collects from users has only increased as time has progressed, but at the beginning, there was a lot of pushback from users on Windows 7 and Windows 8 who were not comfortable with the OS phoning home so often.

Microsoft attempted to address these concerns by releasing a tool called the Diagnostic Data Viewer, which let the user see exactly what telemetry data was being collected and uploaded to Microsoft. The company also added different levels of telemetry collection, which would let users control how much data is sent to Microsoft.

Notably, there was never an option to outright turn off telemetry data collection, but you could reduce it to "basics." Still, to this day, Windows collects vast amounts of telemetry data from users, but most people no longer care or have simply forgotten about it.

Fun fact: Microsoft would eventually bring the same telemetry data collection systems to Windows 7. Not many people know that. So, if you remained on Windows 7 because you didn't agree with Windows 10's telemetry collection, you weren't able to avoid it for long.

The birth of Windows as a Service

While Windows 8 was the first version of Windows to be updated on an annual cycle, Windows 10 took things to a new level with Windows as a Service; an attempt to update the Windows OS with major new features and platform enhancements on a bi-annual basis.

Releasing a new version of the Windows platform two times a year was unprecedented at the time. Windows wasn't exactly known for its excellent in-place upgrade capabilities, and so the release of new feature updates in the spring and fall of every year was often met with issues in the first few years of Windows 10's life.

The first Windows 10 feature update landed just a few months after Windows 10 debuted in July 2015, with the version 1511 release, also known as the Windows 10 November 2015 Update. This update introduced a number of quality-of-life improvements, including dark mode for the first time on Windows desktop.

Windows as a Service would come under fire multiple times during Windows 10's life. Most notably with the Windows 10 October 2018 Update, which was released without sufficient testing and resulted in the update deleting user files post upgrade, with said files being unrecoverable.

This issue caused Microsoft to temporarily pull the update and reevaluate the Windows as a Service schedule, resulting in the company scaling back the major platform releases, while still delivering new version updates. Starting in 2019, instead of two major platform releases for two new version updates, Windows 10 would only get one major platform release, with two version updates based on top of it.

Windows OneCore and form factor diversification

One commendable effort Microsoft conducted with Windows 10 was something called OneCore. It was a true attempt at building a universal Windows core that could scale across any and all device types and form factors. It was an attempt to make Windows ambient, capable of running on any device Microsoft wanted it to.

At the time, OneCore enabled Windows 10 to run on all kinds of form factors, including phones, tablets, Xbox, HoloLens, and IoT devices. It was a valiant effort that paid off from a technical perspective, allowing platforms like Windows 10 Mobile and Windows Holographic to exist, alongside UWP, Microsoft's universal app platform that ran on OneCore-based versions of Windows.

Unfortunately, this effort would end up in vain, as Microsoft ultimately killed most OneCore editions outside of the main desktop operating system and its derivatives. That would lead to Windows only really being viable on desktop and laptop devices, with phones, wearables, and IoT devices mostly out of the picture today.

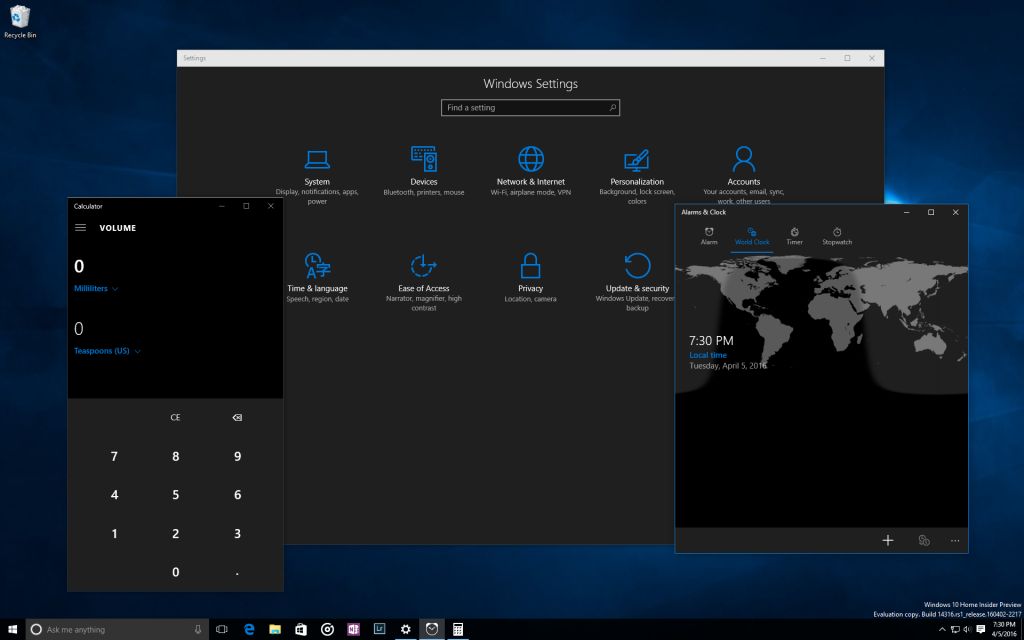

Broken Dark Mode

Windows' modern dark mode issues started here on Windows 10, with the first version of the OS in 2015. When Windows 10 first debuted, it did so with a shell interface that was clearly dark-themed. But the rest of the OS wasn't, including context menus and apps. It wouldn't be until version 1511 that Microsoft would add a dedicated light/dark theme toggle.

In the early days, this toggle only impacted the app theme, which meant even when you set your theme to light mode, the Start menu, Taskbar, and Action Center would remain dark. This wouldn't get fixed until 2018, when the OS would finally get a system-wide theme toggle option.

But even then, this didn't address all of the issues that the dark mode theme had. Many areas of the OS, including copy dialogs and file properties, didn't support light mode, and some areas looked outright broken when dark mode was enabled.

Unfortunately, this was never fixed, not even with Windows 11. To this day, dark mode on Windows is still woefully incomplete, and it was Windows 10 that started it.

Windows 10 fails on phones

Windows 10 Mobile was Microsoft's attempt at bringing Windows 10 to smartphones. It was an evolution of Windows Phone, bringing OneCore and UWP modern Windows-based smartphones. It launched in 2015, four months after Windows 10 in November 2015, to middling reviews due to lacklustre launch hardware and a buggy OS release.

It took Windows 10 Mobile some time to find its footing in the world of smartphones. It wasn't until the Version 1607 release in 2016 that Windows 10 Mobile became stable enough to recommend to users. The OS shared the same universal app platform and core operating system as Windows 10, albeit without the ability to run legacy desktop applications.

It did introduce a feature called Continuum, which let users use their phone like a real Windows PC when docked up to an external display. This feature was years before Samsung DeX and Android Desktop Mode, and was well ahead of the curve.

Unfortunately, due to slow adoption of UWP and Windows 10 Mobile's troublesome launch, the platform failed to gain much traction in its first two years on the market. Microsoft would ultimately pull the plug on Windows 10 Mobile in 2017, indirectly killing UWP in the process.

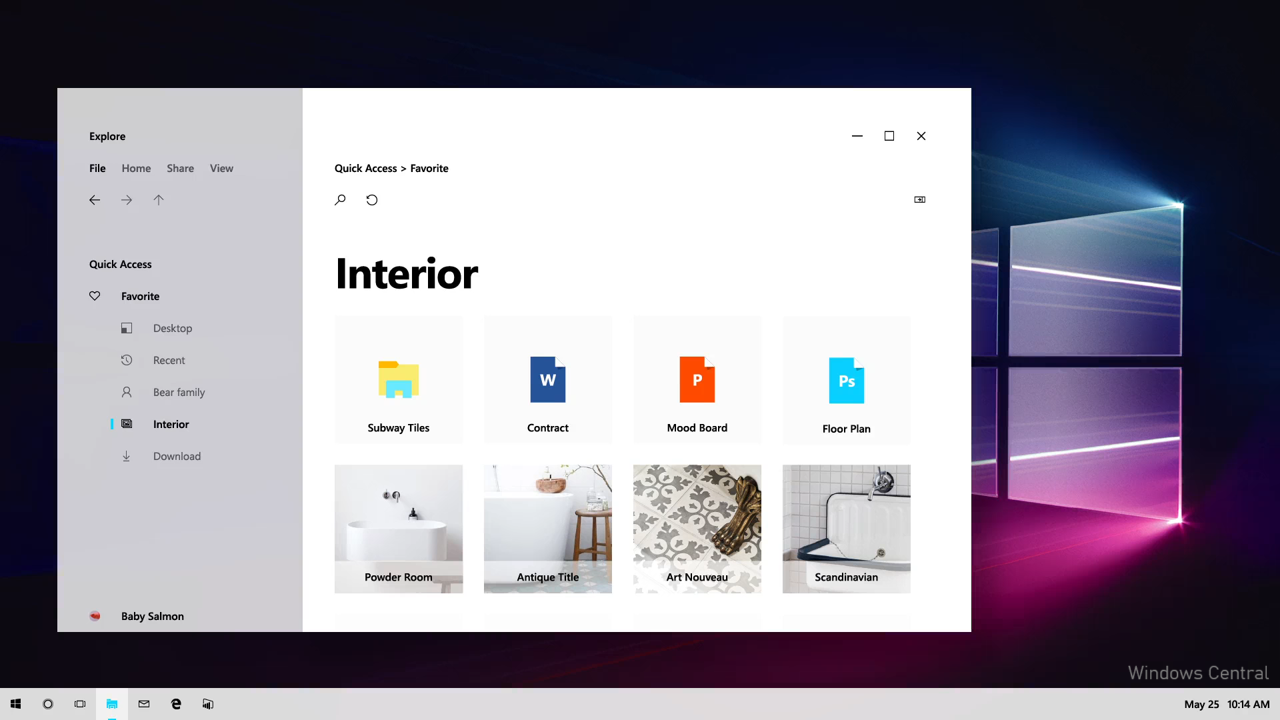

The Universal Windows Platform

UWP was Microsoft's modern app platform that was designed to scale up and down the form factor spectrum. It let developers easily create adaptive apps that would run on Windows 10 Mobile, Xbox, HoloLens, and Windows PCs in a secure sandboxed environment. Unfortunately, UWP was incredibly barebones at launch, missing vital APIs and features that developers needed to build the Windows apps they wanted.

This meant UWP adoption was slow, and it took a very long time for big-name developers to finally adopt UWP. Even then, most didn't, instead choosing to maintain their legacy Windows apps or opting to build a web app instead. The main reason app developers would even consider UWP was because of Windows 10 Mobile.

However, when Microsoft killed Windows 10 Mobile in 2017, that made UWP redundant for a lot of app developers, which slowed adoption of the platform further. This ultimately led to Microsoft winding down support for UWP in 2021, replacing it with WinUI, which is based on Win32 instead.

UWP still exists today in Windows 11 and developers can choose to build apps with if they want, but there are no active features or new APIs in development, and there's no real benefit using it over WinUI.

Fluent Design System (was disappointing)

In 2017, Microsoft announced the Fluent Design System, an attempt to overhaul the Windows UX and broader Microsoft design language with a fresh coat of paint, rooted in the need for UI design that transcended the traditional 2D interface. In a lot of ways, it was very similar to Apple's just-announced Liquid Glass design language, with 3D effects, motion, and fluid animations.

At the time, Microsoft showcased vast new Windows interfaces that were essentially a complete redesign of the Windows desktop. Apps would support 3D flyouts and objects, and the entire desktop interface would be given a fresh coat of paint with the Fluent Design System in mind.

However, when it finally came time to start rolling out the Fluent Design System, what we got was nothing like what Microsoft had promised. At most, it was a subtle update that was most notable in icons, with some blur, lighting, and motion effects applied sparingly across the operating system.

Fluent Design was a huge disappointment for users who were looking for a complete overhaul of the Windows desktop, something Microsoft had promised. To this day, Microsoft still hasn't delivered on most of the designs it showcased in that original Fluent Design System announcement.

It's probably accurate to say that the Windows 11 interface is what Fluent Design became, but it's still nowhere near what Microsoft had originally promised from this new design language.

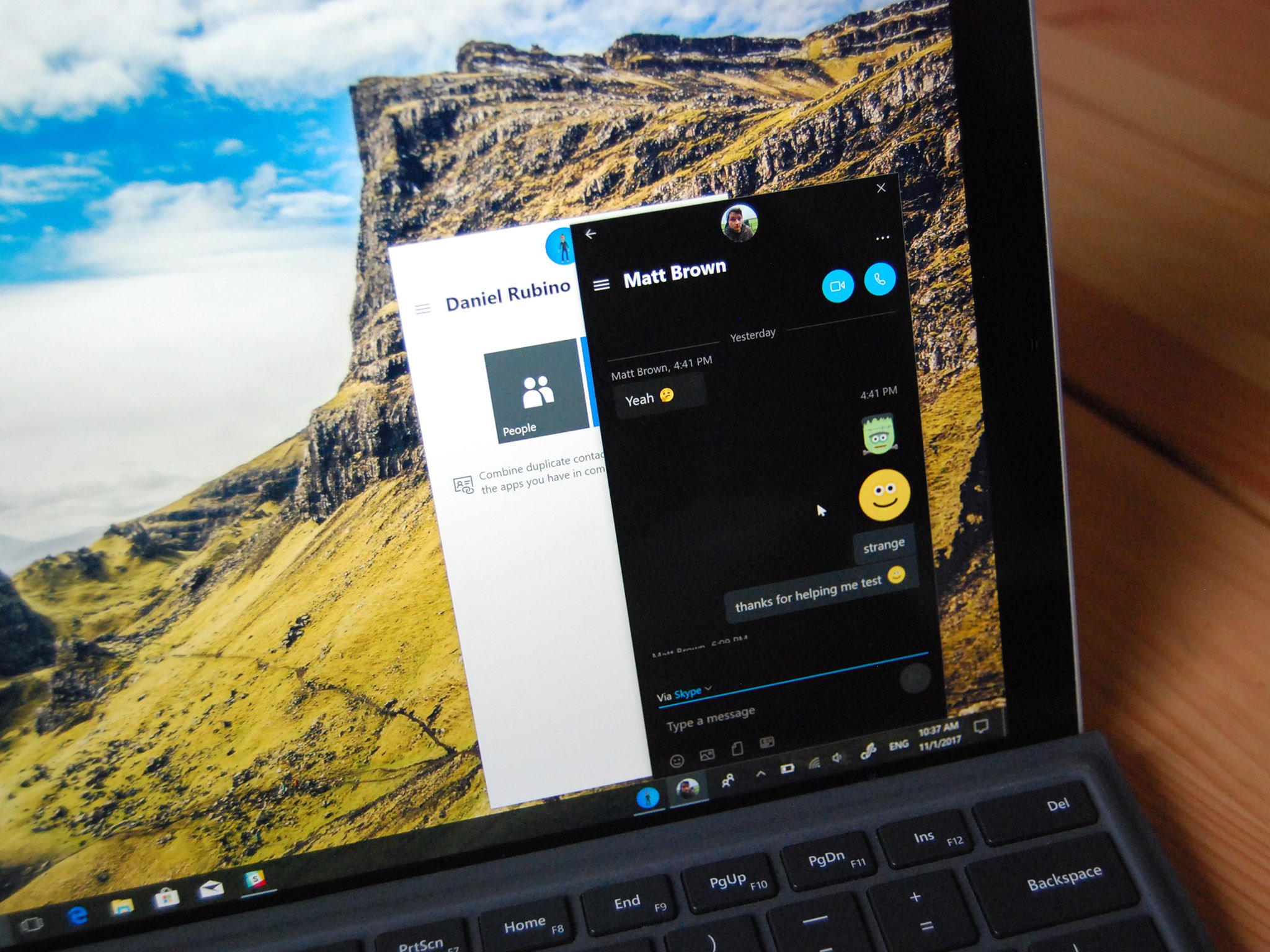

My People was an embarrassment

My People was an interesting attempt at building an iMessage competitor directly into Windows 10. The feature would let you pin contacts directly to your Taskbar, letting you quickly access their contact details and location, or send them a message or file.

The feature was announced and initially supported apps like Windows Mail and Skype. At the time, Microsoft was trying to position Skype as the client to sync your SMS messages with. Pinned contacts could send you nudges that would appear as 3D animations above the Taskbar. Clicking on a contact would open a dedicated person flyout that let you quickly interact with the person without leaving your current app.

My People was also open to third-party developers, which meant apps like Instagram or Twitter could also integrate into the My People flyouts. Unfortunately, basically no third-party developers updated their apps to support My People, which ultimately led to the feature being killed off just a couple of years later.

My People is still present in Windows 10 to this day, but it's now defaulted to being off, whereas it was originally automatically enabled on all Windows 10 PCs.

Windows 10: Defining Windows Today

Windows 10's long tenure on the market is nothing short of impressive, but that also means the OS did a lot more than just 10 things that defined it. Notably, Windows 10 is what killed Microsoft's own web browsing engine, replacing Edge UWP with a version built on Chromium. There's also Your Phone, which began life on Windows 10 and was the first time Microsoft truly embraced Android as an extension of the Windows PC.

Windows 10 did so much to set the narrative for the Windows we have today. It wasn't perfect, and some could argue that Windows 10 killed Microsoft's chances of evolving Windows to run on more than just desktops and laptops, but we believe it brought more to the table than it took away.

Now, Windows 11 is the latest version, replacing Windows 10 even though Microsoft said at the time that Windows 10 would be the last version of Windows. With hindsight, that was a terrible idea. But at least we've got something new to play with now.

Windows 10 will finally be put to rest later this year, as mainstream support comes to an end. Rest in peace, Windows 10.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.